In this Article

- Key Takeaways

- Why is Protein Purification Important?

- Deconstructing the Downstream: The Multi-Step Protein Purification Process

- Foundational Separation Science: Principles of Protein Purification

- The Chromatography Arsenal: High-Resolution Protein Purification Techniques

- Tackling Tough Targets: Challenges in Recombinant Membrane Protein Purification

- Real-Time Quality and Compliance: PAT and Validation

- Conclusion: Refining Purity for Tomorrow’s Therapies

Advanced Protein Purification Methods for Recombinant Biologics

All of the products listed in AAA Biotech’s catalog are strictly for research-use only (RUO).

Key Takeaways

- Cost Driver: Downstream processing accounts for ~75 % of biomanufacturing costs, making purification optimization a financial imperative.

- Purity Mandate: Regulatory bodies demand extremely low levels of Host Cell Proteins (HCPs), often 1–100 ng/mg product (ppm) or lower.

- Workflow Strategy: Purification follows a sequential Capture to Intermediate to Polishing workflow, exploiting orthogonal physicochemical differences.

- Capture Efficiency: Affinity Chromatography (AC), especially Protein A, defines the success of the Capture step due to high selectivity and volume reduction.

- Process Intensification: Multimodal Chromatography (MMC) and Continuous Chromatography (PCC/SMB) are key advanced strategies to increase productivity and resin utilization significantly.

- HIC/IEX Roles: Ion Exchange (IEX) handles charge variants, while Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) separates based on mild hydrophobicity, preserving native structure.

- Membrane Protein Challenge: Integral Membrane Proteins (IMPs) require specialized mimetics like Nanodiscs or Amphipols to maintain native folding stability.

- Quality Control Shift: Process Analytical Technology (PAT) is essential for real-time monitoring and control, enabling Quality by Design (QbD) and supporting continuous processing.

If you are working in biopharma research or therapeutic development, you know the blunt truth: downstream processing (DSP), particularly protein purification, is the single greatest determinant of cost, speed, and ultimately, patient safety. The need to optimize this process is not merely academic; it is driven by a massive financial and regulatory urgency.

Let's begin with the economics. Downstream processing often accounts for approximately 75% of total manufacturing costs in bioproduction. For the global therapeutic protein drug industry, the purification processes alone cost more than $40 billion per year. This staggering figure demonstrates why streamlining the protein purification process and increasing yield without sacrificing quality is a non-negotiable priority for modern biomanufacturing.

“Protein purification” describes a highly controlled series of processes intended to isolate one or a few target proteins from a complex mixture of cell debris, host components, and media additives to fully specify the function, structure, and activity of the molecule.

Why is Protein Purification Important?

The threat of contamination is real for every researcher, and the chances of miscalculation can lead to improper results.

Beyond simple concentration, purification is the quality safeguard. Contaminants pose significant risks, primarily revolving around Host Cell Proteins (HCPs). HCPs are endogenous proteins expressed by the host organism (e.g., E. coli or Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells) used to produce the recombinant therapeutic.

The presence of residual HCPs in the final drug product is a critical quality attribute (CQA) because, as proteins foreign to the human body, they can negatively impact the drug product’s stability and efficacy, or worse, elicit dangerous toxicity or immune responses.

Regulatory bodies, including the FDA and EMA, mandate rigorous control and clearance of these impurities. The industry often sets the target for residual HCPs in the final therapeutic product at a stringent level, typically ranging from 1 to 100 ng HCP/mg product (ppm), with some demanding levels even lower than sub-ppm. This low tolerance means that achieving purification levels that are often 99.9% requires a highly complex, multi-step process.

Regulatory specifications require detailed physicochemical characterization for product identity, purity, and stability. This absolute demand for purity, juxtaposed against the high costs of achieving it, necessitates the adoption of highly efficient and high-resolution protein purification techniques.

Deconstructing the Downstream: The Multi-Step Protein Purification Process

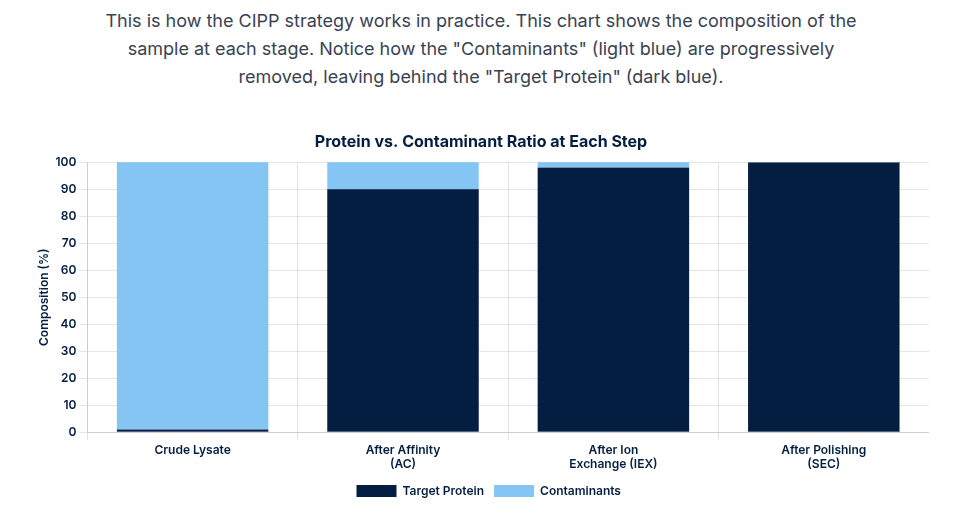

The complexity of the feed stream containing tens of thousands of different proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids means that no single separation step can achieve the required clinical purity.

Therefore, the answer to “How Does Protein Purification Work?” lies in a staged, multi-dimensional strategy designed to exploit orthogonal differences between the target molecule and the impurities.

A. The Preliminaries: Extraction and Solubilization (Protein Isolation and Purification Methods)

The initial phase of the purification process involves preparing the crude mixture.

- Sourcing and Expression: Recombinant proteins are produced in expression systems (e.g., E. coli, yeast, or mammalian cells).

- Cell Lysis: The cells must be broken open to release the target protein (Extraction). Methods include non-enzymatic, mechanical, disruption (sonication, French press), or enzymatic/chemical methods (lysozyme, detergent reagents).

- Stabilization: Immediately following lysis, stabilization is critical. This involves inhibiting degradation using broad-spectrum protease and phosphatase inhibitors and maintaining controlled buffer systems, optimal pH, and ionic strength.

For challenging targets, such as membrane proteins (which are often hydrophobic), the extraction requires specialized detergents for solubilization. Careful control over ionic conditions and temperature is necessary throughout these intermediate stages to avoid protein reduction, aggregation, or instability, which compromises final recovery.

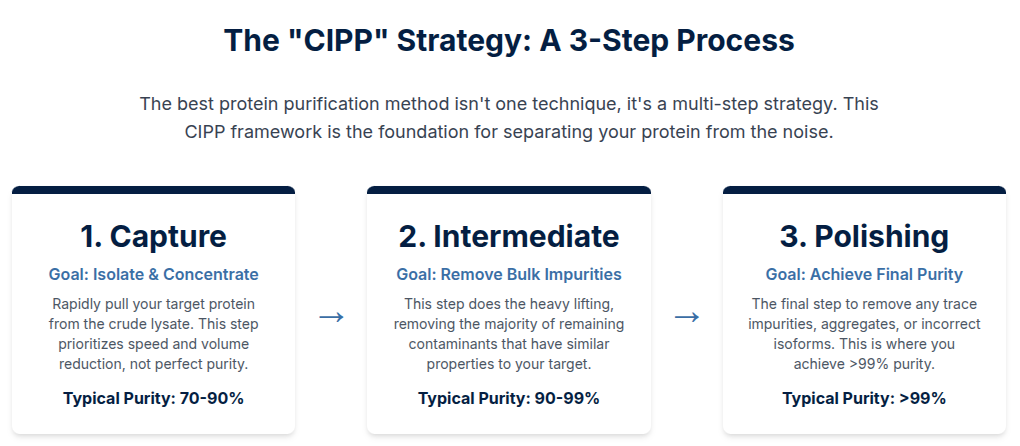

B. The Foundational Workflow: The Protein Purification Steps

The protein isolation and purification methods in biopharma strictly follow a sequential, three-stage workflow: Capture, Intermediate Purification, and Polishing. The objective is to rapidly concentrate the product and sequentially clear impurities, particularly those categorized as high-risk "Bad" and "Ugly" contaminants.

Table 1: The Four Essential Protein Purification Steps in Downstream

| Stage | Goal | Primary Separation Principle | Typical Methodologies | Purity/Volume Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capture | Rapid isolation, concentration, and stabilization of the target molecule. | High Specificity Affinity Binding | Affinity Chromatography (AC, e.g., Protein A, IMAC), Precipitation. | High yield, 50–90% purity, major volume reduction. |

| Intermediate Purification | Bulk impurity removal (HCPs, nucleic acids, aggregates, truncated product). | Charge, Hydrophobicity, or Mixed-Mode | Ion Exchange (IEX), Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC), Multimodal (MMC). | Purity >95%, efficient contaminant clearance. |

| Polishing | Trace impurity removal, separation of closely related product variants (e.g., deamidation isomers, aggregates). | High Resolution Size or Charge | Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC), High-resolution IEX, Hydroxyapatite (CHT). | Ultra-high purity (up to 99.9%), meets regulatory CQA targets. |

| Formulation | Buffer exchange, concentration, and preparation for storage or final drug substance. | Membrane Separation | Ultrafiltration/Diafiltration (UF/DF). | Final concentration (tens of mg/mL), stability checks. |

The efficiency of the initial Capture step, often using affinity chromatography, is paramount. This step must be rapid and high-capacity because it immediately reduces the volume and complexity of the crude lysate, alleviating the burden on subsequent, less-specific steps. If the Capture step is optimized for high yield and contaminant clearance, the entire downstream train benefits, ensuring acceptable step yields, which typically need to be maintained at 80–90% for commercial processes.

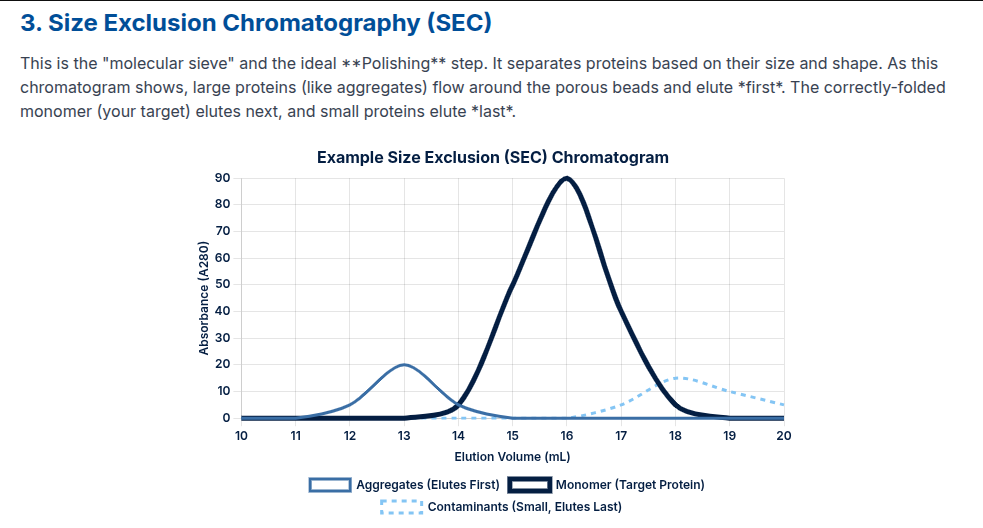

The final Polishing steps are where the highest cost and time are often incurred. Techniques like Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) or high-resolution Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEX) are necessary not just for general cleanup, but specifically for separating closely related product variants (such as aggregates or deamidation isoforms) that share high chemical similarity with the target.

Removing these trace impurities is mandatory because they directly threaten product stability and may lead to immunogenicity, making the Polishing stage crucial for meeting stringent clinical specifications.

Foundational Separation Science: Principles of Protein Purification

The successful selection and sequencing of purification techniques relies entirely on understanding their fundamental principles, which exploit intrinsic differences between the target molecule and its contaminants.

A. The Principles and Reactions of Protein Extraction, Purification, and Characterization

Chromatography, which employs a mobile phase passing through a stationary phase (matrix), remains the core tool for high-resolution separation. Separation is based on four core physicochemical interactions:

- Affinity (Specific Binding): This relies on a highly selective, reversible biological interaction between the target molecule and a specific ligand coupled to the matrix. This 'lock-and-key' selectivity often results in thousands-fold purification in a single step.

- Charge (Ion Exchange): Proteins are separated based on their net charge at a given pH, which determines their interaction with oppositely charged resins (anion or cation exchangers).

- Hydrophobicity: Separation uses a mildly hydrophobic stationary phase. Target proteins with exposed hydrophobic amino acid side chains bind to the matrix.

- Size/Shape (Steric Exclusion): Proteins are separated according to their hydrodynamic volume. Larger proteins are excluded from the porous beads of the matrix and elute first, while smaller proteins travel a longer path within the pores and elute later.

B. Non-Chromatographic Methods: Scale Enablers

While chromatographic techniques provide the necessary resolution, non-chromatographic methods are essential for initial bulk reduction and sample handling, particularly for large volumes. These protein isolation and purification methods enable the use of smaller, less expensive chromatography columns later in the process.

- Precipitation: Simple, inexpensive methods often using high salt concentrations (e.g., ammonium sulfate) or organic solvents. Although it yields lower purity and incomplete recovery, it is highly cost-effective for initial large-scale fractionation and concentration.

- Membrane Separations (UF/DF): Ultrafiltration (UF) concentrates the protein, while Diafiltration (DF) facilitates buffer exchange by removing salts and small molecules. This is crucial for adjusting buffer conditions between chromatography steps (e.g., lowering salt concentration after HIC before IEX) and for the final concentration phase.

The decision to use high-throughput non-chromatographic techniques in the early stages is a critical bioprocess engineering trade-off. By significantly reducing the initial volume of the process stream, the cost and size of the subsequently required chromatography media, which are the primary cost drivers in DSP, are drastically lowered.

The Chromatography Arsenal: High-Resolution Protein Purification Techniques

The effective DSP train relies on selecting and sequencing the right protein purification techniques to address specific impurity challenges.

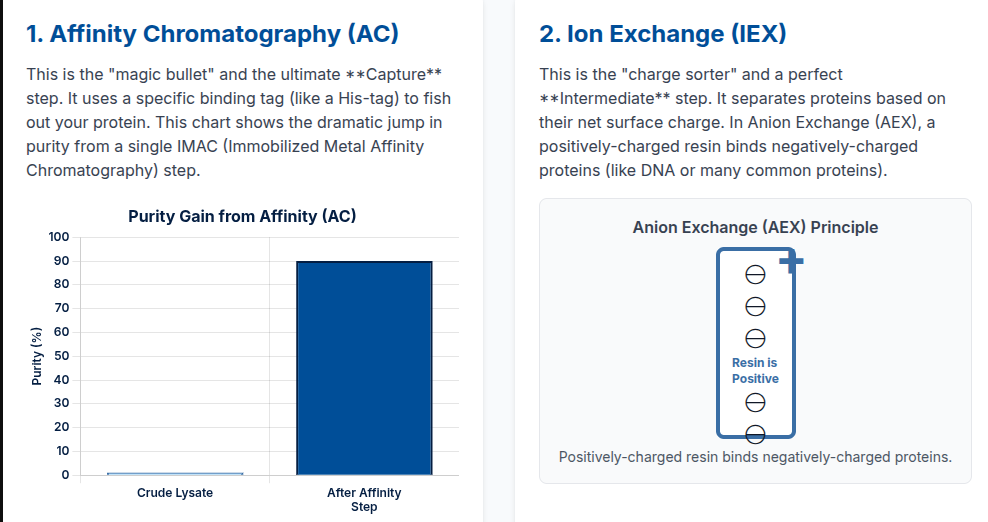

A. Affinity Chromatography (AC): Capturing the Recombinant Target

Affinity chromatography is the defining Capture step for most recombinant proteins due to its unparalleled high selectivity.

-

Tag-Based Purification:

For laboratory-scale and some commercial applications, recombinant proteins are engineered with defined peptide sequences (epitope tags) fused to the target, allowing for specific capture.

-

His-Tag (Polyhistidine):

Commonly used for both soluble and membrane proteins, often employing Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC), where the tag binds to chelated metal ions.

-

GST-Tag:

Purified via glutathione-coupled matrices.

-

His-Tag (Polyhistidine):

Commonly used for both soluble and membrane proteins, often employing Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC), where the tag binds to chelated metal ions.

-

Therapeutic Antibody Purification:

For Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs), the established gold standard is Protein A chromatography (or Protein G), which binds specifically to the Fc region. This single step provides high specificity and often high yield, with elution typically achieved by a pH shift (low-pH buffer).

However, the tag selection and elution conditions must be optimized, as non-native sequences or harsh elution buffers can negatively affect the protein’s folding and activity.

B. Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEX): Charge-Based Resolution,

IEX separates proteins based on their net charge at the working pH. It is one of the most flexible techniques, capable of performing capture, intermediate, and final polishing duties.

- Mechanism: Anion exchangers bind negatively charged proteins, while cation exchangers bind positively charged proteins. The elution of bound proteins is achieved by gradually increasing the ionic strength (salt concentration) of the mobile phase, which weakens the electrostatic interaction with the resin.

- High-Resolution Application: IEX offers exceptional resolution, capable of separating molecular species that possess only minor differences in charge properties, such as two proteins differing by a single charged amino acid. This makes it indispensable for clearing charge variants that are closely related to the therapeutic product.

C. Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC): Mild Separation

HIC separates proteins based on surface hydrophobicity.

Mechanism: Binding occurs at high concentrations of "salting-out" salts (e.g., ammonium sulfate), which promote the interaction between exposed hydrophobic patches on the protein and the mildly hydrophobic stationary phase. Elution is performed by decreasing the salt concentration.Advantage: A unique advantage of HIC is that it provides high-resolution separation in a nondenaturing mode, preserving the protein’s tertiary structure and biological activity. It is often used as an intermediate step, complementing IEX and AC.

D. Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Polishing and Formulation

SEC, or gel-filtration chromatography, separates proteins based purely on hydrodynamic size.

- Application: SEC provides lower resolution and capacity compared to affinity or ion exchange and is therefore generally used in the final Polishing step or for buffer exchange. Its primary high-value function is the efficient removal of soluble aggregates and dimers from the monomeric drug product, ensuring final product size homogeneity.

The success of how protein purification works in modern biopharma is often determined by the implementation of an orthogonal multi-step workflow. By sequencing techniques that leverage different characteristics, the process ensures that any impurity escaping the first step is captured by the second, allowing the final product to meet the stringent sub-ppm purity standards.

Table 2: Principles and Performance Metrics of Classic Protein Purification Techniques

| Chromatography Mode | Separation Principle | Elution Mechanism | Selectivity/Resolution | Typical DSP Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affinity (AC) | Highly specific reversible binding (Ligand-Target) | pH shift or competitive ligand (e.g., imidazole) | Extremely High | Capture, Primary Purification |

| Ion Exchange (IEX) | Reversible electrostatic interaction (Net Charge) | Increasing Salt (Ionic Strength) or pH shift | High (Separates minor charge variants) | Capture, Intermediate, Polishing |

| Hydrophobic Interaction (HIC) | Surface hydrophobicity | Decreasing "Salting-Out" Salt Concentration | Medium | Intermediate Purification (Non-denaturing) |

| Size Exclusion (SEC) | Hydrodynamic size and shape | Isocratic Buffer Flow | Low (Excellent for aggregates/buffer exchange) | Polishing, Final Formulation |

The high cost of column chromatography resins and the pressure from high-titer upstream bioreactors have necessitated a paradigm shift toward intensified downstream strategies. These techniques are increasingly considered the best methods for manufacturing scale, offering massive gains in productivity.

A. Multimodal/Mixed-Mode Chromatography (MMC)

Multimodal chromatography (MMC) is a versatile separation technique that utilizes stationary phases engineered with ligands capable of more than one interaction, typically combining ion exchange (charged groups) and hydrophobic interactions (aliphatic/aromatic groups).

- Dual Selectivity: By employing multiple modes simultaneously, MMC achieves enhanced selectivity, allowing for the efficient removal of complex mixtures and difficult process impurities (HCPs, nucleic acids) in a single step.

- Salt Tolerance: A key operational advantage is the ability to handle high-salt conditions. Unlike traditional IEX, MMC often permits salt-tolerant adsorption of the target protein, allowing direct capture from crude or high-conductivity feedstocks without the need for extensive dilution or intermediate buffer adjustments.

- Process Streamlining: The combined mechanism allows a single MMC column to perform the function of two traditional columns (e.g., replacing a sequential IEX and HIC step), significantly reducing the number of unit operations and overall process time.

B. Continuous Chromatography (PCC and SMB)

Conventional packed-bed chromatography is recognized as a major productivity bottleneck. Continuous chromatography methods, such as Periodic Counter-Current (PCC) and Simulated Moving Bed (SMB), provide an industrialized solution to this problem.

- Principle of Counter-Current Flow: These methods simulate the movement of the stationary phase (resin) counter-current to the mobile phase (feed) by sequentially shifting the position of the feed inlet and product outlets across multiple small columns.

- Addressing the Upstream Challenge: The success of modern high-titer cell cultures (e.g., 5 g/L mAb feeds) demands a DSP solution that can handle constant, concentrated feed. Continuous systems dramatically increase throughput, with demonstrated feasibility for achieving an order of magnitude increase in productivity compared to batch processing.

Table 3: Comparative Advantages of Continuous vs. Batch Chromatography

| Metric | Batch Chromatography | Continuous (PCC/SMB) | Bioprocess Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Productivity | Lower (limited by column cycle time) | Significantly Higher (Up to 10x increase) | Reduced manufacturing footprint and processing time. |

| Resin Utilization | Inefficient (40–60% capacity saturation) | Highly efficient (up to 90%+ utilization) | Major reduction in media cost, optimizing capital expenditure. |

| Holding Times | Longer, increasing risk of degradation | Fast processing reduces critical holding times | Essential for maximizing stability of labile therapeutic molecules. |

| Product Quality | Excellent purity achieved | Comparable quality (HCP/aggregate clearance) | No trade-off in meeting stringent CQA requirements. |

By utilizing smaller columns and maximizing the capacity saturation of expensive resins (like Protein A), continuous chromatography offers superior process economics. Furthermore, the increased speed and reduced holding times are critically important for unstable molecules.

The ability of MMC resins to combine multiple separation functions further simplifies the engineering of continuous systems, requiring fewer complex manifold configurations and making the integration of the overall protein purification process more feasible.

Tackling Tough Targets: Challenges in Recombinant Membrane Protein Purification

While the strategies above optimize soluble protein purification, integral membrane proteins (IMPs), which account for roughly 25% of human protein-coding genes, present profound, specialized challenges.

A. The Detergent Dilemma and Instability

Membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to study due to their inherently hydrophobic surfaces, flexibility, and limited stability once removed from the native lipid bilayer. To extract them from the cell membrane, researchers must use detergents.

However, detergent-based purification creates a non-native environment that strips away associated native lipids. This destabilizing environment can induce aggregation, misfolding, or loss of function, even if the purification protocol achieves high mass purity. Therefore, optimization efforts must stringently control multiple environmental factors, including temperature, shear force, pH, and ionic conditions, to maintain stability and recovery.

For purification, specialized affinity tags, such as longer histidine tags (e.g., His8 or His10), are sometimes used instead of the standard His6 tag for enhanced capture efficiency.

B. Next-Generation Mimetics for Native Folding

For structural and functional studies, achieving simple mass purity is insufficient; the protein must retain functional integrity in a native-like state. To overcome the limitations of traditional detergents, novel membrane mimetics are employed:

- Nanodiscs: This technology uses engineered scaffold proteins to encircle the IMP with a controlled, native lipid bilayer patch. This approach better preserves the lipid environment and facilitates downstream structural methodologies (e.g., single-particle electron microscopy or cryo-EM), which require homogeneous, non-aggregated samples.

- Amphipathic Polymers (Amphipols/SMALPs): These polymers can extract membrane proteins without the use of detergents, forming a stabilizing polymer belt that keeps the protein soluble and functionally stable in aqueous solutions.

For these highly challenging targets, the protein purification steps must often include a final high-resolution size separation (SEC) to ensure that the functional monomer, stabilized within the nanodisc or polymer, is isolated from any aggregated material before resource-intensive analysis. This highlights that for IMPs, purification strategies focus on functional purity, not just mass clearance.

Real-Time Quality and Compliance: PAT and Validation

Maintaining quality and control throughout the complex, multi-step, protein purification process is mandatory for safety and commercial viability.

A. Regulatory Control and Validation

Regulatory guidance from bodies like the FDA requires that specifications and analytical methods used for product release and shelf life be fully described and submitted. Critical quality attributes (CQAs), such as HCP levels, must be rigorously monitored. Developers must establish a structured, risk-based approach to assessing and mitigating HCP-associated risk. The process development must therefore characterize HCP clearance criteria to thoroughly understand the purification steps and guarantee product quality.

B. Process Analytical Technology (PAT)

The shift toward process intensification and continuous manufacturing necessitates moving beyond traditional retrospective quality control. Process Analytical Technology (PAT) provides the framework for this transition.

- Proactive Quality Control: PAT involves the integration of analytical instruments and methodologies (such as spectroscopy, chromatography, and biosensors) in-line, on-line, or at-line with the manufacturing equipment. The core goal is to enable real-time measurement and control of CQAs during processing.

- Enabling Continuous DSP: PAT is pivotal for operating continuous systems (PCC/SMB) effectively. By enabling continuous monitoring and process control, PAT allows manufacturers to implement Quality by Design (QbD) principles and work toward real-time release (RTR) of the therapeutic product.

This transition from retrospective testing to proactive, real-time control is the final frontier in optimizing the protein purification process. It ensures compliance while simultaneously reducing the financial risks associated with complex, high-cost batch failures.

Conclusion: Refining Purity for Tomorrow’s Therapies

The “separation scientist” stands at the nexus of biological complexity and economic necessity. The goal of mastering protein isolation and purification methods is defined by a dynamic push toward achieving clinical-grade purity (sub-ppm HCPs) with maximized efficiency.

The modern purification process is highly refined, built upon orthogonal protein purification techniques that systematically eliminate contaminants based on affinity, charge, hydrophobicity, and size. We have moved from simple batch separation to highly engineered, integrated workflows.

The implementation of advanced methods like Multimodal Chromatography (MMC), which collapses multiple steps into one by leveraging combined separation mechanisms, and continuous chromatography (PCC/SMB), which drastically increases productivity (up to 10x) and resin utilization, represents the future of large-scale therapeutic protein manufacturing.

Faq's

What is the primary drawback of using Protein A in the Capture step?

The primary drawback is the high cost of the Protein A resin itself, which necessitates efficient, high-capacity loading. Additionally, elution at low pH can sometimes cause product aggregation or denaturation if not carefully controlled.

How does Hydroxyapatite Chromatography (CHT) primarily differ from IEX in its separation mechanism?

CHT separates based on both charge and calcium-phosphate binding sites on the apatite crystal lattice, offering unique selectivity. Unlike standard IEX, CHT is often used for separating charge variants and aggregates while effectively removing host cell DNA, sometimes bridging the Intermediate and Polishing roles.

What is a common analytical method used in-line to monitor the quality attribute of HCP clearance during continuous processing?

A common in-line PAT tool for monitoring impurities like HCPs is in-line UV-Vis or fluorescence spectroscopy integrated near the column outlet. For specific HCP quantification, an at-line High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system coupled with mass spectrometry might be employed for rapid assessment.

In the context of SMB, what does "simulated moving bed" actually refer to?

It refers to the simulation of counter-current flow between the liquid mobile phase and the solid stationary phase (resin). This is achieved by sequentially switching inlet/outlet ports across several smaller columns to mimic continuous resin movement, maximizing resin capacity use.

Why is the successful removal of host cell DNA considered a critical step, even if it's not a protein?

Residual host cell DNA must be cleared to extremely low levels (often <10 ng/dose) because it carries a risk of genotoxicity and potential oncogenicity if present in the final therapeutic product administered to patients.