In this Article

- What is Recombinant DNA and Recombinant Protein?

- How to Produce Recombinant Protein: Expression System Selection

- Genetic Factors Affecting Recombinant Protein Expression

- Protein Folding, Aggregation, and Quality Control

- Host Cell Protein Removal: The Hidden Quality Challenge

- AAA Biotech's Role in Recombinant Protein Excellence

- Conclusion: The Future of Recombinant Protein Manufacturing

Key Factors That Affect Recombinant Protein Yield and Quality

All of the products listed in AAA Biotech’s catalog are strictly for research-use only (RUO).

Major Focuses

- The selection of the host system for protein expression dictates achievable yield, cost, and the fidelity of Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs).

- Correct PTMs, like glycosylation, are critical for the bioactivity, stability, and therapeutic safety of complex proteins.

- Genetic optimization boosts yield because codon optimization and strong promoter selection are high-impact strategies for increasing protein expression levels.

- High-yield bacterial production often forms inactive inclusion bodies, necessitating a costly, low-recovery refolding process.

- Therapeutic proteins require >95% purity, verifiable bioactivity, and minimal Host Cell Protein (HCP) and endotoxin contamination.

- Purification (downstream processing) accounts for 60–75% of total manufacturing costs, making optimization crucial for economics.

The global recombinant proteins market is projected to reach USD 11.32 billion by 2034, up from USD 3.97 billion in 2025 - a powerful indicator of explosive growth in biopharmaceutical manufacturing.

Yet here's the challenge that keeps production managers awake at night: a single percentage-point improvement in yield can translate into millions of dollars in cost savings, while a quality misstep can derail clinical programs entirely.

The stakes are astronomically high. Producing recombinant proteins with consistent, high yield, and exceptional quality isn't just about efficiency - it's about patient safety, regulatory compliance, and competitive advantage.

Whether you're developing insulin analogs, monoclonal antibodies, or novel therapeutic proteins, understanding the factors that impact yield and quality is no longer optional.

The reality is stark: downstream processing alone accounts for approximately 60-75% of total biomanufacturing costs, making every optimization decision critical. At the same time, regulatory agencies demand proteins with purity exceeding 95%, bioactivity verification, proper post-translational modifications, and free of host cell protein contamination - standards that demand precision at every production stage.

This comprehensive guide explores the science and strategy behind optimizing recombinant protein production, diving deep into the factors that separate mediocre results from exceptional ones. Let's begin.

What is Recombinant DNA and Recombinant Protein?

Understanding the Recombinant DNA Definition

Recombinant DNA is engineered DNA created by combining DNA fragments from different sources - often from different species using specialized laboratory techniques. The term "recombinant" refers to the combination of genetic material that wouldn't naturally occur, creating what scientists sometimes call "chimeric DNA" because it can contain material from multiple organisms.

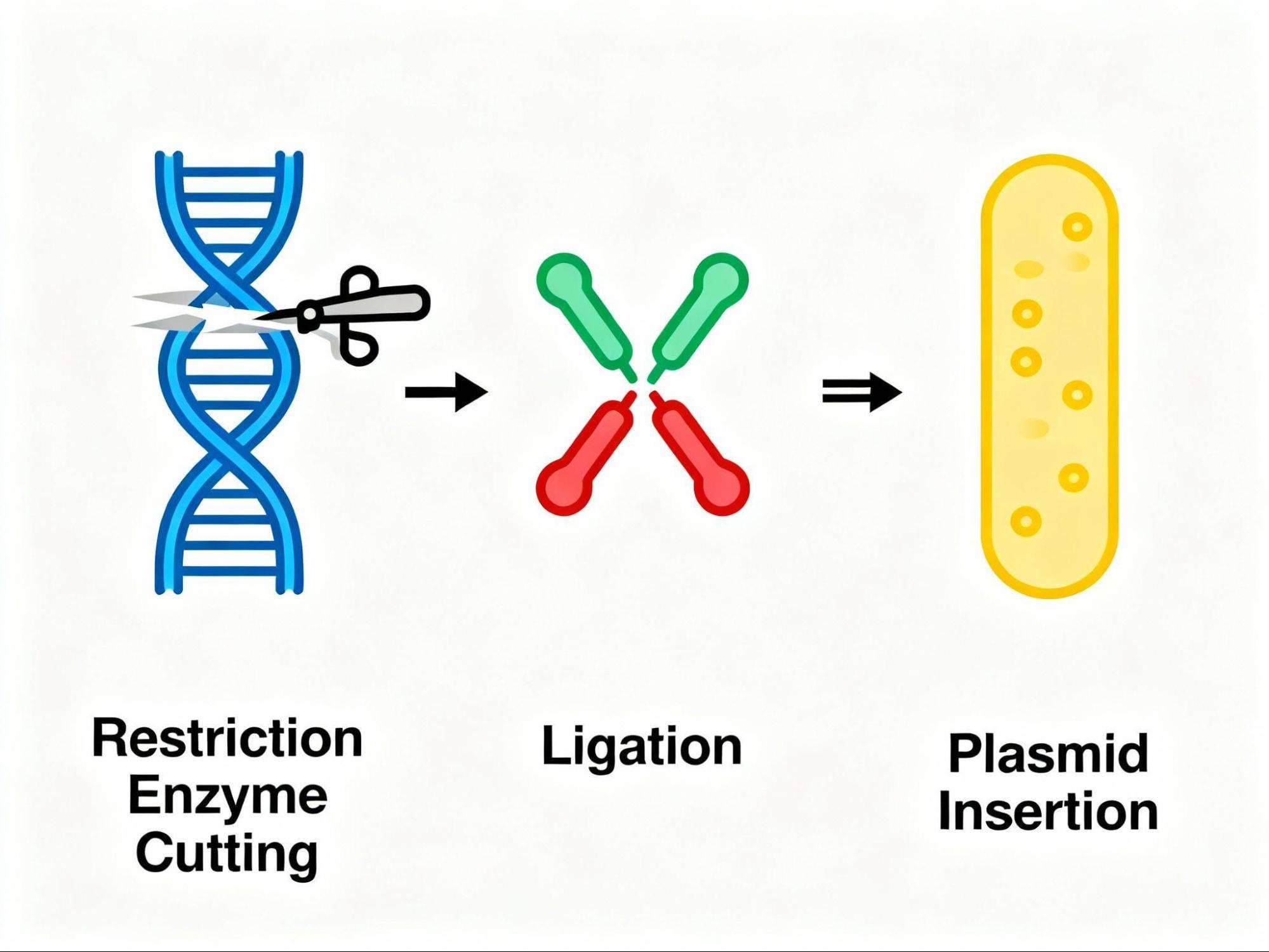

The fundamental principle works because DNA molecules from all living organisms share the same chemical structure; they differ only in their nucleotide sequences. Restriction enzymes (molecular scissors) cut DNA at specific palindromic sequences, creating "sticky ends" that can be joined together using DNA ligase. A cloning vector - typically a plasmid or virus that carries the foreign DNA into host cells, where the cellular machinery replicates and expresses it.

What is Recombinant Protein Expression

Recombinant protein expression is the process of using engineered DNA to direct host cells to synthesize specific proteins of interest. When recombinant DNA encoding a target protein enters a host organism, the cell's transcription and translation machinery translate the genetic code into functional protein molecules.

The beauty of this approach is that scientists can instruct cells to produce virtually any protein - human insulin from E. coli, monoclonal antibodies from mammalian cells, or complex glycoproteins from yeast with remarkable precision and scalability.

Understanding Recombinant Protein Production

Recombinant protein production encompasses the entire manufacturing process: from designing optimized genes through final purification and quality control. It's an intricate orchestration of molecular biology, bioprocess engineering, analytical chemistry, and regulatory science. The goal is straightforward but demanding: to produce therapeutic-grade proteins consistently, reliably, and economically.

How to Produce Recombinant Protein: Expression System Selection

The first critical decision in recombinant protein manufacturing is choosing the right expression system. This choice cascades through every subsequent production parameter and fundamentally determines achievable yield, product quality, timeline, and cost structure.

Recombinant Protein Expression Systems: A Comprehensive Comparison

01. E. coli (Bacterial Expression)

Strengths:

- Highest volumetric productivity in fermentation

- Rapid production (days to weeks)

- Cost-effective at scale

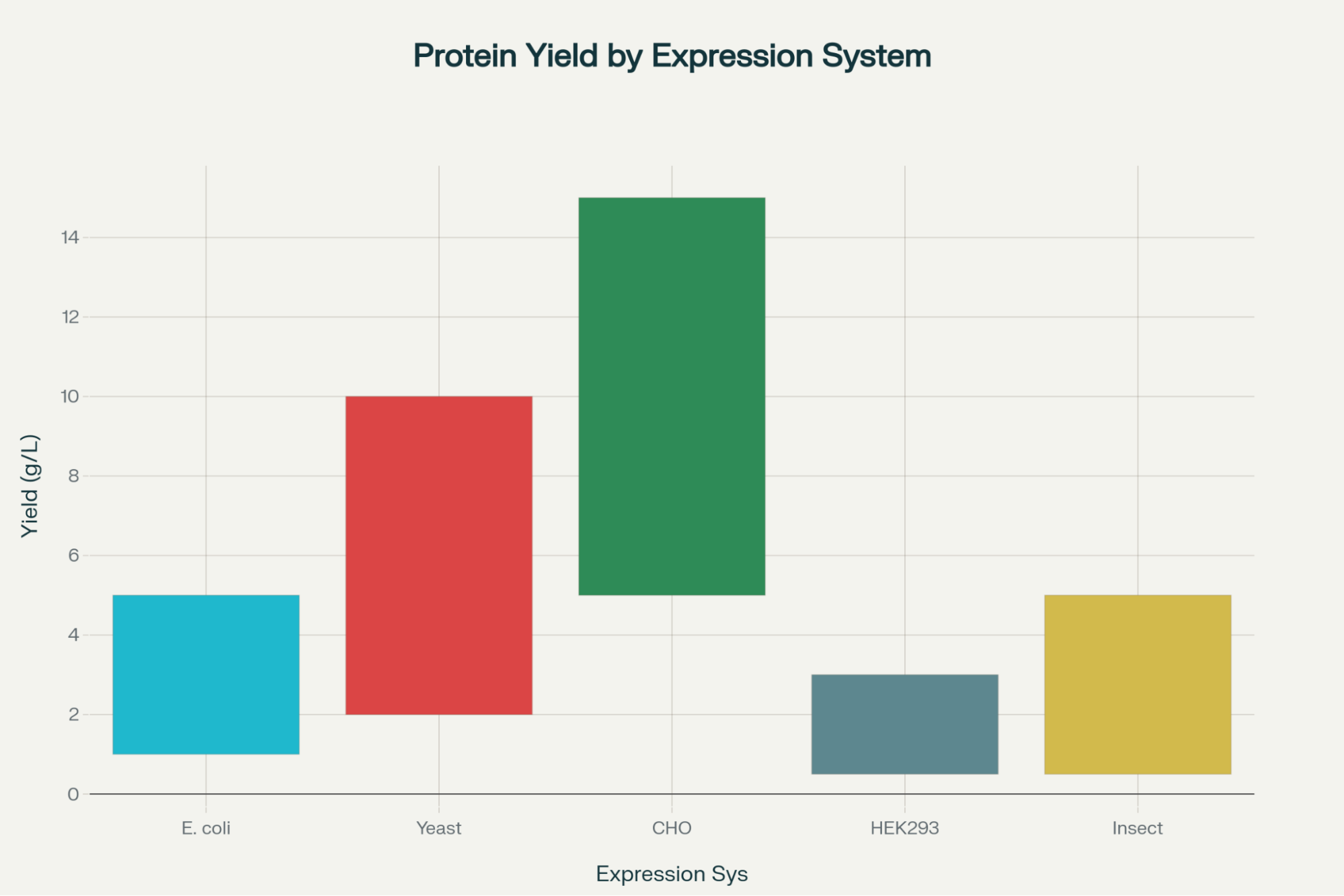

- Produces up to 1-5 g/L in optimized systems

- Simple, well-characterized host

Limitations:

- No post-translational modifications (no glycosylation, phosphorylation)

- Frequent inclusion body formation (misfolded protein aggregates)

- Limited capability for disulfide bond formation

- Produces proteins in the cytoplasm, not the secretory pathway

- Not suitable for complex therapeutic proteins requiring PTMs

02. Yeast Expression Systems (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia pastoris)

Strengths:

- Performs key post-translational modifications (N-glycosylation, O-glycosylation)

- Proteins are naturally secreted into the media (easier recovery)

- 2-10 g/L yield range

- Scalable and economical

- Eukaryotic protein folding machinery

Limitations:

- Glycosylation patterns differ from those of mammalian cells

- Some proteins show heterogeneous modification patterns

- Cannot replicate complex mammalian glycosylation

- Production timelines: weeks

03. Mammalian Cell Expression: CHO and HEK293 Cells

Strengths:

- Highest protein yields: 5-15 g/L (CHO), 0.5-3 g/L (HEK293)

- Mammalian-type complex glycosylation patterns

- Superior protein folding fidelity

- Correct disulfide bonding

- Produces secreted proteins

- Regulatory gold standard for therapeutic biologics

Limitations:

- Highest production costs

- Longest development and production timelines (weeks to months)

- Requires sophisticated bioreactor infrastructure

- Complex cell line development process

- Sensitive to culture conditions (pH, temperature, oxygen)

Real-world data: Industry data shows CHO cell lines routinely achieve specific productivities of 50-100 pg/cell/day, with leading programs reaching 100+ pg/cell/day. This translates to volumetric productivities exceeding 10-15 g/L in extended fed-batch processes.

04. Insect Cell Expression

Strengths:

- Performs insect-type glycosylation (often sufficient for research)

- Baculovirus expression provides high protein levels

- 0.5-5 g/L yield

- Reasonable production timelines

- Good protein folding

Limitations:

- Glycosylation patterns of non-human (immunogenic risk for therapeutics)

- Moderate yield and scalability

- Less suitable for clinical therapeutics

Genetic Factors Affecting Recombinant Protein Expression

Codon Optimization and Codon Bias

Why it matters: The genetic code is degenerate - 64 possible codons encode only 20 amino acids. Organisms strongly prefer certain codons over others (codon bias), and mismatched codon usage between the foreign gene and host cell creates a critical bottleneck.

The mechanism: Rare codons in the host organism are translated slowly because their corresponding transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are scarce.

This creates:

- Ribosome stalling and slow translation elongation

- Increased mRNA degradation

- Incomplete protein synthesis

- Potential translational errors

- Protein misfolding

Impact on yield: Research demonstrates that codon optimization can increase expression levels by 2.8-fold or higher. One landmark study optimizing human interferon-beta (rhIFN-β) for CHO cells by adjusting GC content at the third codon position achieved a 2.8-fold expression increase.

Best practices:

- Match codon usage to high-expression genes in the host organism

- Optimize GC content (typically 45-55% is favorable)

- Preserve slow-translating regions that facilitate proper protein folding

- Avoid problematic mRNA secondary structures

- Validate computationally before synthesis

Promoter Selection and Strength

The promoter's role: Promoters control transcriptional initiation and directly determine mRNA abundance. Selecting a strong, constitutive promoter (T7, CMV, SV40) versus an inducible promoter (tac, ara, tet-responsive) represents a fundamental production decision.

Optimization strategies:

- Hypomethylation of DNA in promoter regions improves transcriptional activity

- Acetylation of histone proteins enhances active gene transcription

- Preventing promoter methylation through chromatin remodeling increases stability

- Combining promoter elements with regulatory regions (enhancers) boosts expression

Empirical data: Studies show promoter optimization contributes 12-25% yield improvements, making it one of the higher-impact variables.

Expression Vector Design

Vector characteristics affecting yield

01. Plasmid copy number: Higher copy numbers generally increase expression, but excessive copies create a metabolic burden.

02. Selectable markers: Integration of antibiotic resistance genes (ampicillin, kanamycin) affects cellular growth.

03. Integration site: Random genomic integration (in mammalian cells) causes position effects - the same construct produces different expression levels depending on chromosomal location.

04. Multi-copy transgenes: Contrary to what one might expect, higher transgene copy numbers don't always correlate with higher productivity.

Practical impact: Expression vector optimization contributes 10-18% yield improvements.

Signal Peptide and Protein Localization

01. Critical finding: Transport to the endoplasmic reticulum represents the rate-limiting step in the secretory pathway. Signal peptide sequence efficiency directly determines secretion rates.

02. Optimization factors:

- Signal peptide sequence affects translocation efficiency into the endoplasmic reticulum

- Inefficient translocation causes miscleavage of the signal peptide

- Poor ER targeting results in intracellular retention and misfolding

- Optimized signal peptides dramatically improve secretion rates

Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs): Beyond the Gene Sequence

What are PTMs? Post-translational modifications refer to covalent enzymatic modifications proteins undergo during or immediately after synthesis, such as glycosylation, phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, ubiquitination, and proteolysis. These modifications dramatically alter protein structure, function, stability, and immunogenicity.

PTM impact on quality:

- N-glycosylation on therapeutic proteins affects bioactivity, serum half-life, and immunogenicity

- O-linked glycans improve colloidal stability and reduce aggregation

- Phosphorylation activates or inhibits protein signaling functions

- Disulfide bonds stabilize protein tertiary structure

Protein Folding, Aggregation, and Quality Control

Molecular Chaperones and Protein Folding

The folding challenge: Newly synthesized polypeptide chains are at high risk of misfolding, forming non-functional conformations or aggregating with other misfolded proteins. Cells deploy sophisticated molecular chaperone systems to prevent these types of catastrophes from manifesting.

Key chaperone families:

01. Hsp70 (DnaK in bacteria, BiP in ER): Binds hydrophobic regions of nascent proteins, preventing aggregation

02. Hsp60 (GroEL/ES complex): Creates confined chambers for protein folding

03. Unfolded protein response (UPR): Cellular stress response upregulating chaperones when misfolding reaches critical levels

Major challenges:

- Overexpression creates a metabolic burden exceeding available chaperone capacity

- Hydrophobic protein regions are prone to aggregation

- Complex proteins requiring specific cofactors may misfold in heterologous hosts

Inclusion Bodies: Challenges and Opportunities

What are inclusion bodies? They are insoluble aggregates of overexpressed recombinant protein that accumulate as dense cytoplasmic deposits in bacterial cells (particularly E. coli). While often viewed as failures, inclusion bodies contain surprisingly high protein concentrations.

Proteomic analysis reveals:

- Recombinant protein content: typically 85-95% of total protein in inclusion bodies

- Associated host proteins: Heat shock proteins (IbpA, IbpB), some chaperones (DnaK, GroEL)

- Minor impurities: Traces of phospholipids, nucleic acids

- Protein fragments: Truncated or modified species from proteolysis

Refolding workflow for inclusion bodies:

1. Purification to homogeneity: Isolate inclusion bodies from soluble cellular proteins

2. Solubilization: Denature aggregates with chaotropic agents (guanidinium chloride, urea)

3. Refolding: Dilute into refolding buffer, allowing spontaneous renaturation

4. Purification: Further chromatography to obtain the final product

Read to learn more about: Advanced Protein Purification Methods for Recombinant Biologics.

Recombinant Protein Quality Metrics

Quality attributes demanding attention:

01. Purity (typically >95% for therapeutics)

- Assays: SDS-PAGE, size-exclusion chromatography (SEC), mass spectrometry

- Contaminants: host cell proteins, endotoxins, aggregate species

02. Potency/Bioactivity (must equal or exceed reference standard)

- Cell-based assays (functional assays measuring specific biological activity)

- Receptor binding assays (ligand-receptor interaction validation)

- Enzymatic assays (for enzyme products)

- Regulatory requirement: Must validate for each lot

03. Identity (confirms correct protein product)

- Mass spectrometry (intact mass, peptide mapping)

- Amino acid sequencing (N-terminal sequence verification)

- Isoelectric focusing

04. Post-translational Modification Profile

- Glycosylation mapping (LC-MS analysis of released N-glycans)

- Phosphorylation site characterization

- Disulfide bond pattern verification

- Critical for biologics since PTMs affect bioactivity 5-100 fold

05. Homogeneity (degree of consistency)

- Dynamic light scattering (DLS) for size consistency

- Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy for secondary structure

- Analytical ultracentrifugation

- Monomer percentage by SEC-HPLC

06. Safety Parameters

- Sterility testing (absence of microbial contamination)

- Endotoxin quantification (LAL assay, <175 EU/kg for IV therapeutics)

- Bioburden assessment

Host Cell Protein Removal: The Hidden Quality Challenge

Understanding Host Cell Proteins (HCPs)

Host cell proteins are contaminating proteins originating from the expression host (E. coli, CHO, HEK293) that co-purify with the recombinant product.

Even trace residual HCPs (ng/mL concentrations) can:

- Compromise safety (immunogenic reactions, aggregation promotion)

- Impair efficacy (HCP-drug interactions)

- Trigger regulatory rejections

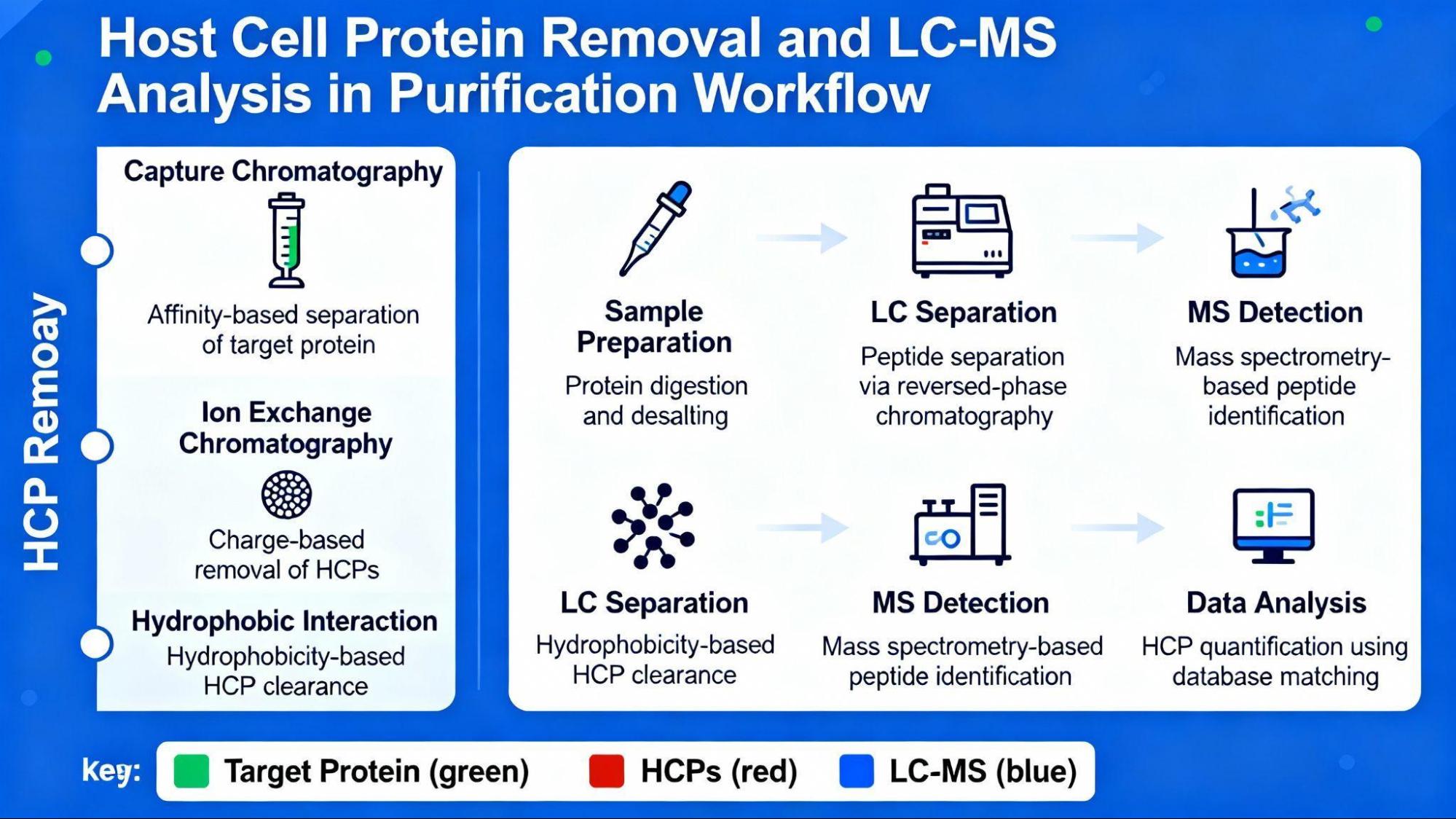

HCP Removal Efficiency

Depth filtration studies (CHO host systems):

- X0SP filter (polyacrylic fibers + synthetic silica): >600 g/m² binding capacity for positively charged HCPs

- Progressive reduction through purification: crude extract → affinity capture → secondary purification → final product

- Final residual HCP: typically <100 ng/mg target protein (regulatory requirement)

LC-MS for HCP Profiling

Advanced technique:

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) enables individual HCP identification and quantification, providing:

- Specific HCP species identification (not just total protein)

- Individual quantification (vs. ELISA total quantification)

- Process understanding and optimization guidance

- Risk assessment of immunogenic species

AAA Biotech's Role in Recombinant Protein Excellence

AAA Biotech specializes in producing premium recombinant proteins and reagents for biomedical research. With an extensive portfolio of 600+ recombinant antibodies and 6,000+ ELISA kits, AAA Biotech understands the nuances of producing high-quality, well-characterized biological reagents.

AAA Biotech's recombinant protein features:

- High Purity: 95%+ purity verified by SDS-PAGE and affinity chromatography

- Proven Bioactivity: Functionally tested across multiple applications

- Multiple Expression Systems: Prokaryotic (E. coli) for simple proteins; eukaryotic (HEK293, CHO) for complex therapeutic proteins

- Flexible Tagging: His-tag, GST-tag, FLAG-tag, Fc fusion options for detection and purification

- Quality Control: Rigorous validation using SEC, DLS, and potency assays

Explore AAA Biotech's recombinant protein catalog to discover pre-characterized, production-ready proteins for your research.

Conclusion: The Future of Recombinant Protein Manufacturing

The global recombinant proteins market's explosive growth to USD 11.32 billion by 2034 reflects the transformational power of this technology. Yet the industry continues advancing, and emerging trends include continuous biomanufacturing (replacing traditional batch processes), artificial intelligence-driven process optimization, and real-time quality monitoring, replacing batch release testing.

Success in recombinant protein manufacturing demands integration of molecular biology, bioprocess engineering, analytics, and regulatory science. Every decision from expression system selection through final purification cascades through your production metrics, your costs, and ultimately, if relevant, patient outcomes.

Whether you're optimizing academic research, developing clinical programs, or manufacturing commercial biologics, the principles outlined here provide a science-based framework for maximizing yield while ensuring the exceptional quality that modern medicine demands.

Faq's

Q1: What is the primary trade-off when selecting an expression system?

The core trade-off is speed/cost versus biological fidelity. Simple bacterial systems offer rapid, inexpensive, high-yield production but lack crucial eukaryotic Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) required for complex protein function and quality.

Q2: How does temperature affect soluble recombinant protein yield in E. coli?

Lower induction temperatures (e.g., 12–15°C) increase the time available for molecular chaperones to assist in proper folding, significantly increasing the yield of soluble, active protein and reducing misfolding into inclusion bodies. Production at 39°C to 44°C results in 15% to 20% insoluble protein.

Q3: Why is glycosylation critical for therapeutic recombinant protein quality?

Glycosylation, performed authentically only in eukaryotic systems like mammalian cells, affects protein stability, solubility, and most importantly, biological activity and circulatory half-life. Incorrect or non-human glycosylation (hyper-mannose in yeast) can lead to antigenicity.

Q4: What is the typical yield expectation for affinity purification (AC)?

Affinity chromatography (AC), especially using tags like His-tag, provides high specificity and rapid capture, leading to excellent recovery. Typical recovery yields for well-expressed, tagged proteins often exceed 90% in the initial capture step, greatly facilitating subsequent purification.

Q5: How does AI/ML improve recombinant protein production?

AI/ML models enhance yield by predictive modeling of complex bioprocess factors, such as nutrient utilization and cellular metabolism. This allows researchers to rapidly identify optimal culture media and feed strategies, minimizing empirical testing and maximizing productivity with a high precision (R = 0.9973).